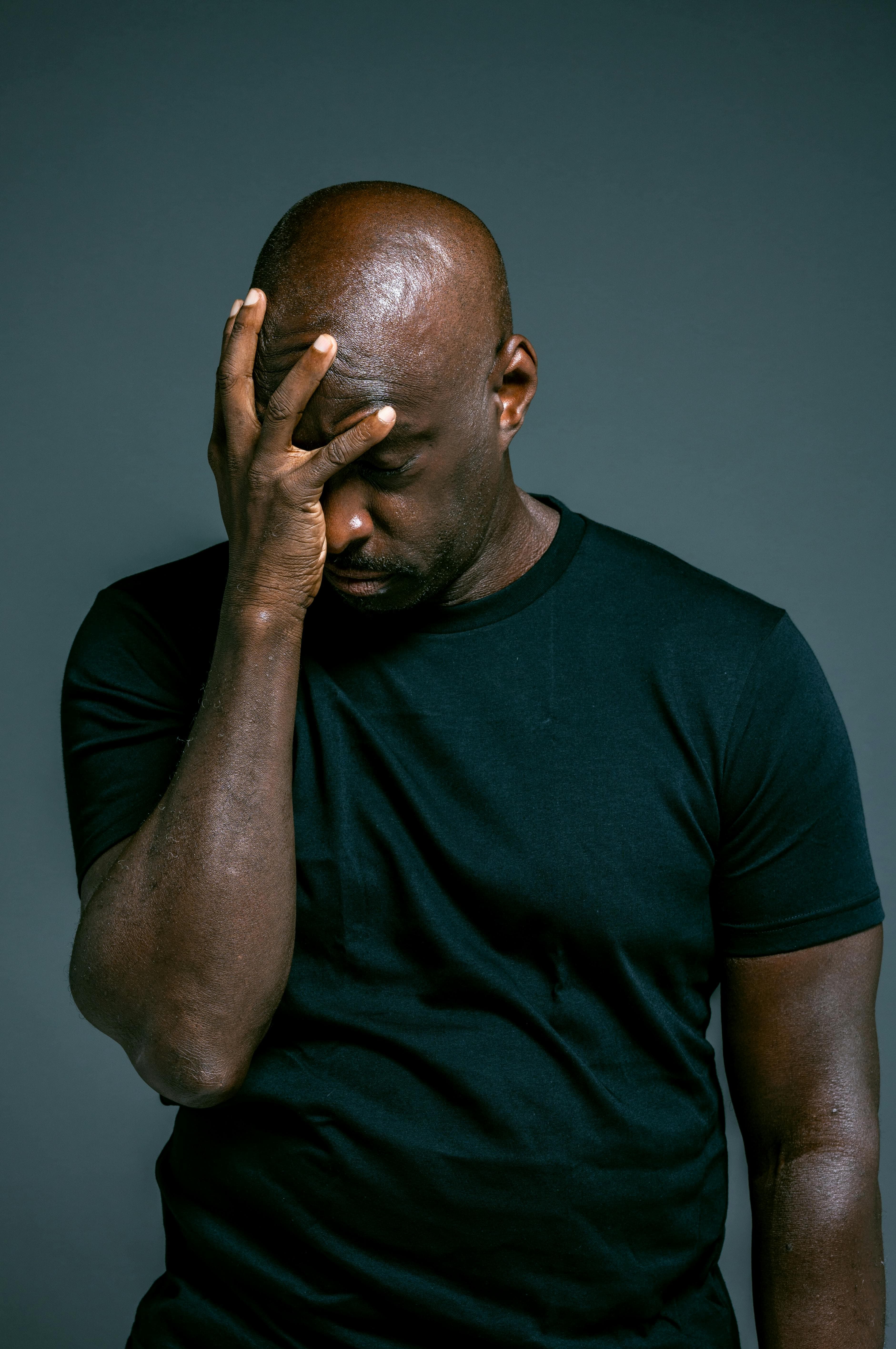

"Any minute now, they're going to realise I have no idea what I'm doing."

James shifted in the chair opposite me, looking genuinely puzzled that I wasn't more concerned. He'd just been promoted to director level at a FTSE 100 company—his third significant promotion in five years. Colleagues sought his opinion. Senior leadership mentioned him in succession planning conversations. By every external measure, he was thriving.

Internally? He was waiting for the tap on the shoulder. The awkward conversation. The moment everyone would discover what he already knew: that he'd somehow fooled everyone, and it was only a matter of time before the truth came out.

This is imposter syndrome in its purest form. The conviction that you're less capable than others perceive you to be, that your achievements are flukes, and that exposure as a fraud is imminent.

What makes it particularly insidious is that success doesn't cure it. Often, success makes it worse.

TL;DR: Key Takeaways

- Imposter syndrome affects an estimated 70% of people at some point in their lives

- It's most common among high achievers, not those who are actually incompetent

- Five distinct types have been identified: perfectionist, expert, soloist, natural genius, and superhuman

- Women and minority groups often experience it more intensely due to systemic factors

- The syndrome perpetuates itself through avoidance, overwork, and discounting success

- Recovery involves reframing thoughts, gathering evidence, and tolerating discomfort

The Psychology Behind Feeling Like a Fraud

The term "imposter phenomenon" was coined in 1978 by psychologists Pauline Rose Clance and Suzanne Imes, who initially studied high-achieving women. They noticed a pattern: accomplished women frequently attributed their success to luck, timing, or deceiving others about their abilities—anything except actual competence.

Subsequent research revealed that imposter syndrome affects all genders, though women and individuals from marginalised groups often experience it more intensely. A 2020 systematic review found that approximately 70% of people will experience imposter feelings at some point in their lives.

What's particularly striking is who experiences it most. Imposter syndrome doesn't typically afflict the genuinely incompetent—research suggests that people who are actually unqualified tend to overestimate their abilities (a phenomenon known as the Dunning-Kruger effect). Instead, imposter syndrome targets people with genuine achievements, qualifications, and capabilities.

Dr Valerie Young, author of The Secret Thoughts of Successful Women, puts it bluntly: "The only people who don't feel like imposters are actual imposters."

The Five Types of Imposter Syndrome

Not all imposter experiences look the same. Dr Young identified five distinct patterns, each with its own triggers and coping mechanisms:

1. The Perfectionist

For perfectionists, even 99% success feels like failure. They set impossibly high standards, then feel fraudulent when they inevitably fall short. If they do achieve their goals, they dismiss the achievement—they should have done even better, or it wasn't really that impressive.

This type of imposter syndrome is closely linked to perfectionism, where the fear of failure drives impossible standards that can never truly be met.

Triggers: Any mistake, however minor. Feedback that isn't wholly positive. Achieving less than they feel they "should" have.

Pattern: "If I were really competent, I wouldn't have made that error."

2. The Expert

Experts feel they must know everything before they can consider themselves competent. There's always another qualification to earn, another book to read, another skill to master. They feel fraudulent because their knowledge has gaps—ignoring that everyone's knowledge has gaps.

Triggers: Being asked a question they can't answer. Encountering someone who knows more about a topic. Starting any new role before feeling "ready."

Pattern: "I don't know enough to be in this position."

3. The Soloist

Soloists believe that real achievers do everything themselves. Asking for help is evidence of inadequacy. They feel fraudulent when they need support, collabouration, or guidance—things that are normal and necessary in any complex work.

Triggers: Needing to ask for help. Receiving mentoring or support. Not being able to figure something out independently.

Pattern: "If I were really capable, I wouldn't need anyone's help."

4. The Natural Genius

Natural geniuses measure competence by how easily things come to them. Struggling means you're not naturally talented; having to work hard is evidence of inadequacy. They feel fraudulent when success requires effort—even though effort is how humans actually develop competence.

Triggers: Tasks that don't come easily. Taking longer than expected. Needing to practice or revise.

Pattern: "If I were really smart, this wouldn't be so hard."

5. The Superhuman

Superhumans feel they must excel in every role simultaneously—employee, parent, friend, partner, community member. Anything less than exceptional performance in all areas proves they're not good enough. They often work longer and harder than anyone else, trying to prove they deserve their position.

Triggers: Dropping balls in any area of life. Taking breaks. Saying no. Any form of self-care.

Pattern: "Everyone else seems to manage all this. Why can't I?"

| Type | Core Fear | Typical Behaviour | Trigger |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perfectionist | Making mistakes | Sets impossibly high standards | Any imperfection |

| Expert | Not knowing enough | Constantly seeks more qualifications | Knowledge gaps |

| Soloist | Needing help | Works alone, refuses support | Requiring assistance |

| Natural Genius | Struggling | Avoids challenges that don't come easily | Effort required |

| Superhuman | Not excelling everywhere | Overworks across all life domains | Any dropped ball |

Why Imposter Syndrome Sticks

Understanding why imposter feelings persist—often despite overwhelming evidence of competence—requires looking at the psychological mechanisms that keep them in place.

The Self-Reinforcing Cycle

Imposter syndrome creates its own evidence through a clever trap:

- You face a challenge (presentation, project, new responsibility)

- Fear kicks in: "I'm going to be exposed as incompetent"

- You either overwork or procrastinate (different responses to the same fear)

- You succeed (because you're actually competent)

- You attribute success to the wrong thing: "I only managed because I worked all weekend" or "I got lucky" or "They didn't notice my mistakes"

- Imposter feelings remain intact despite the success

- The next challenge triggers the same fear

Notice how success doesn't break the cycle—it actually feeds it. The imposter mind finds ways to discount every achievement, ensuring the underlying belief ("I'm not really capable") remains unchallenged.

Selective Memory

Imposter syndrome involves a biased memory system. Mistakes, criticisms, and failures are remembered vividly and revisited frequently. Successes, praise, and achievements are forgotten almost immediately or explained away.

This creates a distorted picture: your mental record is full of evidence for inadequacy and nearly empty of evidence for competence.

The Spotlight Effect

People with imposter syndrome tend to assume others are watching them closely and will notice any mistake. In reality, most people are too focused on their own performance to scrutinise yours. Research consistently shows we overestimate how much attention others pay to our flaws.

Who Is Most Vulnerable?

While imposter syndrome can affect anyone, certain factors increase vulnerability:

Gender and Stereotypes

Although imposter syndrome affects all genders, research suggests women often experience it more intensely. This isn't because women are inherently less confident—it's because they frequently work in environments where they receive subtle (and not-so-subtle) messages that they don't belong.

When you're the only woman in a meeting, or one of few in your field, external feedback reinforces internal doubt. Stereotype threat—the pressure of potentially confirming negative stereotypes—adds an extra cognitive load.

Ethnic and Cultural Background

Research by Dr Kevin Cokley at the University of Texas found that imposter syndrome correlates with discrimination experiences. When you regularly encounter messages—explicit or implicit—that people like you don't succeed in certain spaces, it's harder to own your legitimate place in those spaces.

First-generation professionals, immigrants, and people from working-class backgrounds also report higher rates of imposter feelings, particularly in elite institutions or industries.

High-Achieving Families

Paradoxically, growing up in high-achieving families can increase imposter vulnerability. If achievement was the currency of belonging—if love and approval seemed conditional on performance—the stakes of any failure feel catastrophic.

Similarly, being labelled "the smart one" or "the talented one" in childhood creates pressure to maintain that identity. Struggle or failure doesn't feel like a normal part of learning; it feels like losing your essential self.

Transitions and New Roles

Imposter feelings typically intensify during transitions: starting a new job, getting promoted, returning to work after parental leave, changing careers. These are moments when competence genuinely needs to develop, but the imposter mind interprets normal learning curves as evidence of fundamental inadequacy.

The Real Cost of Imposter Syndrome

Living with imposter syndrome isn't just uncomfortable—it has measurable consequences:

Career impacts: Fear of exposure leads people to avoid promotions, turn down opportunities, and play small. Research shows imposter syndrome negatively affects career planning and job satisfaction.

Mental health: Strong associations exist between imposter syndrome and anxiety, depression, and burnout. The constant vigilance of waiting to be "found out" is exhausting.

Relationships: Difficulty accepting compliments, reluctance to share struggles, and perfectionist tendencies can strain personal relationships.

Physical health: Chronic stress from imposter syndrome contributes to insomnia, tension headaches, and other stress-related conditions.

Reduced risk-taking: When failure feels like exposure of fundamental inadequacy, avoiding risks becomes logical. This limits growth, creativity, and achievement—ironically reinforcing the very feelings of inadequacy the risk-avoidance was meant to prevent.

Breaking the Imposter Cycle

Recovery from imposter syndrome isn't about suddenly feeling confident. It's about building a more accurate self-assessment and learning to tolerate discomfort without letting it derail you.

1. Recognise the Pattern

Simply naming imposter syndrome can be powerful. When the fraudulent feelings arise, try labellling them: "This is imposter syndrome talking." This creates distance between you and the thoughts, reminding you that feelings aren't facts.

2. Collect Counter-Evidence

Your brain is selectively remembering failures and forgetting successes. Fight back with data:

- Keep a "wins" file: emails of praise, successful project outcomes, positive feedback

- Write down compliments you receive (you won't remember them otherwise)

- Before major events, review your qualifications and past successes

- Ask trusted colleagues for honest feedback on your strengths

3. Reframe the Narrative

When you hear yourself explaining away success, pause. Notice the explanation. Then consider alternatives:

| Imposter Explanation | Alternative Explanation |

|---|---|

| "I got lucky" | "I prepared well and seised an opportunity" |

| "They made a mistake hiring me" | "They assessed me and made an informed decision" |

| "I fooled them" | "I presented myself accurately and they valued it" |

| "Anyone could do this" | "My specific skills and experience made this possible" |

| "I worked so hard—that's the only reason" | "I worked hard AND I have genuine ability" |

4. Separate Feelings from Facts

Imposter syndrome involves a feeling of fraudulence, not evidence of it. Learning to distinguish between "I feel incompetent" and "I am incompetent" is crucial.

Ask yourself: What is the evidence that I'm incompetent? Not feelings—actual evidence. Usually, there isn't any. Or the "evidence" is things like "I made a mistake once" or "I don't know everything"—which apply to every human who has ever lived.

5. Talk About It

Imposter syndrome thrives in silence. When you share your feelings with trusted others, you typically discover two things: they experience similar feelings, and they see you as far more competent than you see yourself.

This doesn't mean announcing in every meeting that you feel like a fraud. It means confiding in mentors, friends, therapists, or colleagues you trust.

6. Redefine Competence

If your definition of competence is "knowing everything, never struggling, never needing help," you've set yourself up for permanent fraudulence. No one meets that standard.

More realistic definitions might include:

- Knowing how to find answers when you don't have them

- Being willing to learn and adapt

- Acknowledging limitations while leveraging strengths

- Contributing your perspective and skills to collabourative work

Learning to treat yourself with kindness during moments of self-doubt is crucial. Our guide on self-compassion offers practical strategies for developing a kinder inner voice.

7. Act Despite the Feelings

Ultimately, imposter syndrome recovery isn't about waiting until you feel confident to take action. It's about taking action while feeling like an imposter, and letting the evidence accumulate.

Every time you succeed despite feeling fraudulent, you build evidence against the imposter narrative. Over time, the feelings may not disappear entirely, but they lose their power to control your behaviour.

What Therapy Offers

Imposter syndrome often connects to deeper patterns: perfectionism, childhood experiences of conditional love, internalised messages about who "deserves" success. Therapy can help untangle these roots.

In therapy, we might explore:

- Where did the imposter beliefs originate?

- What evidence supports and contradicts these beliefs?

- How is imposter syndrome affecting your life and choices?

- What would change if you acted as though you belonged?

- How can you build a more stable sense of self-worth?

Person-centred therapy is particularly valuable here because it offers an experience of unconditional positive regard—being accepted for who you are, not what you achieve. This can be genuinely transformative for someone whose sense of worth has always been tied to performance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is imposter syndrome a mental illness?

No, imposter syndrome is not a clinical diagnosis in the DSM-5 or ICD-11. It's a pattern of thinking and feeling that can occur in otherwise mentally healthy people. However, when severe, it can co-occur with anxiety, depression, or burnout, and it may benefit from professional support.

Does imposter syndrome go away on its own?

Sometimes imposter feelings diminish naturally as people gain experience and evidence of competence. However, for many people—particularly those with deeply ingrained patterns—the feelings persist despite success. Active intervention (through self-help strategies or therapy) is often needed to break the cycle.

Can successful people really have imposter syndrome?

Absolutely—in fact, high achievers are particularly susceptible. Success creates more opportunities to feel fraudulent, and the stakes feel higher. Some of the most accomplished people in the world have spoken about imposter syndrome, including Maya Angelou, Albert Einstein, and Michelle Obama.

How is imposter syndrome different from low self-esteem?

Imposter syndrome specifically involves feeling fraudulent about achievements—believing that your success is undeserved and that others have been deceived about your competence. Low self-esteem is broader, involving generally negative self-evaluation that may or may not relate to achievement or competence.

Is imposter syndrome more common now than before?

Research suggests it may be increasing, particularly among young people. Contributing factors likely include social media comparison, increased competition in education and work, and broader economic uncertainty. However, it's also possible that we're simply more aware of it and more willing to discuss it.

If you're struggling with self-doubt and don't have access to therapy, our guide to the best free mental health resources in the UK includes support options that may help.

Moving Forward

Imposter syndrome tells you that you don't belong, that your achievements are flukes, that exposure is imminent. But here's what the evidence actually shows: you are where you are because of real capabilities, real effort, and real value. The feelings are lying.

James, the client I mentioned at the beginning, didn't wake up one morning suddenly confident. What changed was his relationship to the imposter feelings. They still showed up—particularly before important presentations or after mistakes—but they lost their authority. He learned to notice the feelings, acknowledge them, and proceed anyway.

"The imposter is still there sometimes," he told me near the end of our work together. "But I've stopped believing everything he says."

If you recognise yourself in this article, please know that imposter syndrome is common, treatable, and not a reflection of actual incompetence. You're not a fraud—you're a capable person with a particularly harsh inner critic.

Ready to Explore This Further?

Our integrative counselling approach helps address imposter syndrome at its roots—not just managing symptoms, but exploring where these patterns came from and building a more accurate, compassionate self-perception.

Sessions are available in person in Fulham (SW6) or online across the UK. Book a free 15-minute consultation to discuss how therapy might help you silence the imposter and own your achievements.

If you're struggling with thoughts of self-harm or suicide, please contact Samaritans immediately on 116 123, available 24/7.

Related Topics:

Ready to start your therapy journey?

Book a free 15-minute consultation to discuss how we can support you.

Book a consultation→